How do I begin to tell you what it felt like to go back? I spent every day of my life up to that point dreaming of my homeland. I populated it with every fantasy imaginable. It would be there that I would be safe. It would be there that I would be loved. It would be there that I would finally feel sheltered from the tortuous storms of my youth.

I believed, truly believed, that it would bring an end to the ceaseless longing that had haunted my entire life. I thought that, for the first time, I would find a people among whom I would belong. I thought that I would find my family, and the litany of questions I had carried with me throughout the years since I was sent away would finally be answered. It was the last and, really, only great hope of my life. After all those years of manning the farthest outposts of alienation, I was going to return home. I hungered for a taste of what home was supposed to be. I wanted to savor the salt of Koreanness on my tongue. To roll those emotions around my mouth and feel the satisfaction of belonging drip down the walls of my heart. At that point, I had lived so many lives as so many different people, and I desired to be only myself. I would slip past the flaming sword into my own private Eden. I would eat the overripe fruit of my history, and be free of the lonely wilderness. Of course, dreams are a poor substitute for reality. And when I finally returned to Seoul after a lifetime away, I would discover just how foolish my dreams had been.

I was sent away on November 17, 1984. Adopted to America and erased from Korea.

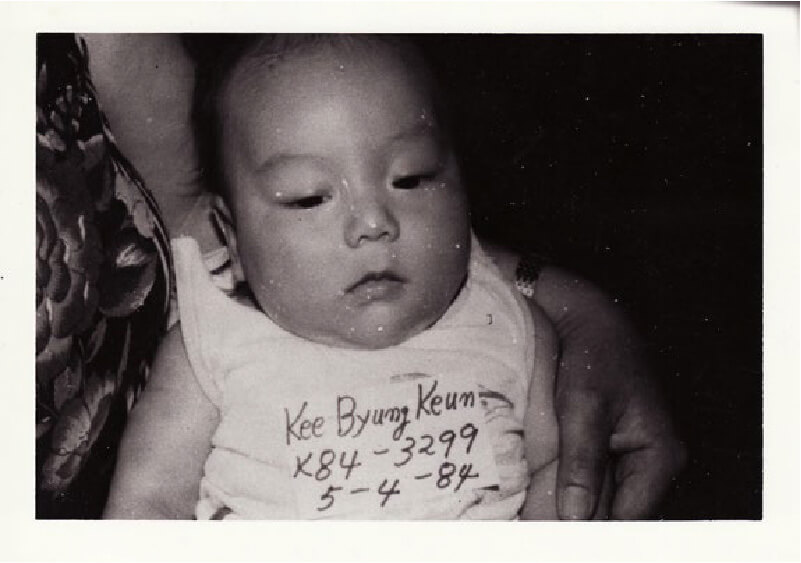

When I arrived in the States, I was given a new name. An American name. A name that would not make anyone uncomfortable in the rural Louisiana backwater where I was taken. From then on, I would no longer be Kee Byung-keun. That identity would be put into hibernation for many years, and I would have to live as Clayton Glen Franks.

Of the constellation of scars on my soul, few have been as stubborn and painful as the name that was forced upon me. Said plainly, I hate it. Sanctified by legal bureaucracy and minutia, there is no easy way to rid myself of it. But oh, how I have dreamed of tearing this brand from my body, because ensconced in those lily white syllables is the spectre of the good American child I could never be. A son of the American South and not South Korea. A son for whom country roads would be a place of comfort and nostalgia, not anxiety and fear. I was given a white name to paint over what I was. But it never saved me from the unfortunate fate of being a minority in America, and within that alabaster cage, I burned.

For years, I was asked if that was my real name. They wouldn’t believe it, always assuming that there was something more. No one is comfortable with not knowing. Secrets make people uneasy. Like they are missing out on something important. Or worse, they worry the secret may be about them. And, of course, the suspicions are not unfounded. The name I used in America was always little more than make believe. I am not who I say I am. I never have been. But behind the constructs of this endless fiction are even deeper lies.

There is no one actually named Kee Byung-keun. It was merely another person’s projected idea about who I should be. A function of paperwork, not of heritage or love. There is no family that it is attached to. No long line from whose threads I have spent my life dangling. It is merely another symbol of my dispossession. Another reminder of all the things that were taken away.

I had spent every day of my life laying amid the bones of my story. What were talked about as hopes, were really fears. Not so much the fear that no one would ever call me home. But the fear that I was already there, and there would never be anyone else. That all my home would ever be was an empty house. Every day, I was filling my mouth with ashes, thinking that it would eventually turn into food. But when I could no longer stand the growl of my empty heart, I decided it was time to go back to Seoul to try and find something that would sustain me. If I was to survive, I had to leave.

It was still dark when I went to the airport. The rain was cold and the roads were empty. I did not look back as I disappeared into the terminal. What no one realized then was that this would be the last time they ever really saw me. Though my body would return soon enough, my spirit never crossed back over the Pacific again. It was the beginning of the end to my American life.

One of the few things that accompanied me from Korea as a baby was a small coin worth ten won. As I sat there that morning waiting to board my first connecting flight, I wished that I had it in my pocket to bring back with me. I would need something to pay the ferryman when it came time to cross the Styx. Instead, I would have to offer something else. Perhaps I could sign away my name or even my memories. There were so many things I wanted to be rid of then, and if giving up any of it would have brought me closer to home, I would have done it with glee. By the time I made it to the gate for the final leg of my journey, I was ready to leave everything behind.

It was November in Northeast Asia, the same month in which I’d been sent away, and when I stepped off the plane, it was cold. I can still remember the way the air bit into my skin. I can remember how the light rushed into my eyes like the water from a broken dam. I was home again. This was the country that birthed me, and every nerve ending in my body switched on to absorb it. Very little of those first moments has been lost in the intervening years. The anxiety, the anticipation; the frenzy of people outside of arrivals and the thickening guilt of not being able to speak to anyone in a language I should have known.

In my gut, I can still feel the heady mix of nausea and excitement as the bus left the airport for downtown. I can still see the flight attendant sitting a few rows in front of me. I can still feel the exhaustion in her bones and see the subtle slump of her shoulders, contrasted against her crisp celadon bow. I remember how full my eyes felt as we crossed the Han, and the city which was once and maybe still is supposed to my home bloomed in front of me. Every car swimming around us and every light flying above has been etched into the rigid bedrock of my mind. For the first time in my life, I was where I was. My footsteps were not echoing in some other city in some other country. I was there alone, and I had no idea what to do with a feeling like that.

Up to that point, I could count the Koreans I had known on one hand. Their presence amounting to little more than comets passing through the edges of my world. It bothered me deeply that I knew no one like me. It was as if every mirror I had ever stood in front of refused to reflect me. How can you know who you are if you cannot even see yourself? You live this life long enough, and you begin to ask whether or not you are even real. Am I a ghost? Am I an illusion? Among the many fictions that have burned across the surface of my life, is it possible that my own body is also an invented reality? You wonder and wonder and wonder, and then one day you look up and the mirror breaks.

I started walking. I had no idea where I was. I didn’t know what I was supposed to do, but I was looking. I couldn’t read anything. I couldn’t speak to anyone. I couldn’t do anything but propel myself forward, because everything behind me had begun to dissolve. There was no border to this image. No line that I would cross that would jar me awake. Along every possible axis, this place that I had dreamed of for so long sprawled out in front of me. And in every face, I could finally see my own. I was not a foreigner. I was from here.

The gravity of belonging pulled at every part of my body that first night. As a child, I was beat up for my eyes and my skin. I was dirty, ugly, and unwanted. I had been force fed a hatred for myself by a world that was willing to buy my body, but not respect it. I was ridiculed, slurred, mocked. I was derided as an interloper and a pretender. How dare I play at being American, because Americans do not look like I do. Every action of every day had become an act of defense. I felt endlessly besieged by a world that loathed me, and I could never be without my armor, because vulnerability was not something I could afford.

Even at home, among the people that raised me, I was alone. None of them knew what it was like to not be white. None of them knew what it was like to be constantly questioned as to why they were there and why they looked like they did. There was no refuge. There was no solace. No matter where I went or who I was with, no one understood the burden on my shoulders. No one could guide me through the storm of racism and prejudice that battered me everywhere I went. I was alone in my battle. I was alone in my pain.

So as I moved my body through the streets of Seoul, I felt something I had never experienced. Slowly and bit by bit, the armor that had accreted around me began to melt away. There had been no time in my life, no place I had been where everyone was Korean. Barely twenty-four hours before, I was still trapped in the cell of my American imprisonment, but here I was free. My race no longer mattered. It was not that I felt equal in the eyes of those around me. It was indifference. It didn’t matter to anyone that I was Korean, because they were all Korean too.

Every story has a beginning, and every story has an end. Before I became Clayton Glen Franks, I was Kee Byung-keun. Before I was Kee Byung-keun, I was someone whose name I do not know. I can only assume that someone, somewhere knows the name I was born with. But who they are and what they know are mysteries that will chase me to the grave.

On August 4, 1984, the continuity of my history was broken. The story as it was being told came undone, and a baby boy was abandoned in Yeongdeungpo Station on the south side of Seoul. There was no information. No note. No possessions. Only a yellow bag with a few diapers in it. Someone found the boy and took him in for the night. But the next day he was surrendered to the police and absorbed into the adoption system, in which he was processed and eventually sold to people in a country half a world away.

And so, I began where everything ended. On the morning of my first full day, I boarded the train and went back to Yeongdeungpo to see where it happened, to see where everything changed. I wanted to see if I could put myself back in the same physical place and perhaps remember something about that time. I wanted to remember something about the day when everything went wrong. Because while the narrative as it was recorded had no oxygen left in it, it was my body that had born witness to it. I had been in that place before. Someone had held me. Someone had found me. Someone had brought me in from somewhere and decided that this was the best possible place to leave a baby that was still too young to walk. It’s indulgent to think that this kind of memory is possible, because no one remembers that time in their life. But trauma does unusual things to the brain, and I really believed that being there would break the seal on the black box I was keeping these things in. I thought that I could defy the event horizon of my past and reach into the black hole with both hands to exhume the remnants of who I was before.

I walked every inch of every corridor I could find. I looked behind signs and into open lockers. I walked up and down the stairs and rode every escalator in and out of the station. I circled the building twice, and I wandered the neighborhood outside. I still think of a particular passage that was cordoned off. Its lights were dimmed until about halfway down where they came on again. I stood there for a long time thinking that this is either a metaphor or a warning, because down there where the lights came back on must be where my ghost was being kept.

In the end, I just sat in the waiting area for the express trains watching the passengers come and go. I thought that, if I waited long enough, I would see someone important. More than that, I wanted someone to see me. I wanted to be recognized by someone. I wanted someone to see my face and remember that day from twenty-six years before when they left me there with nothing. I was still in Yeongdeungpo; I still wanted to be found.

No one did. But from then on I developed the habit of looking at everyone on whatever train I would be on, wandering if this person sitting next to me might be the one that I had been searching for. Wandering if this person sitting next to me had also been searching for me.

There was a moment in my time there when I looked in the mirror of my hotel bathroom and I did not recognize the person I saw. Change normally takes time. Changing a habit or a lifestyle can take years, but sometimes change doesn’t take long at all. Before August 4, 1984, I had a history and an identity, but on August 5th, I had nothing. After all those years of thinking I would go home to Seoul and become who I was supposed to be, I found myself becoming someone else.

A new ache developed in my heart. In those long, lonely days when I couldn’t talk to anyone about anything, when I spent my mornings lost in the city and my afternoons languishing in my room, I felt the ache of almost. Here I was in the city of my birth, but because of the thick wall of the things I did not know, I was inhabiting it at a distance. I was almost there, but I didn’t know how to close the gap. I was almost Korean, but I didn’t know how to be one. I was almost home, but I didn’t know exactly where that was. I was finally somewhere that I should have belonged, but it was still just an almost. Something was still missing. I was not enough.

The initial relief of being among my people after so long away decayed into a nebulous disorientation. Everyone needs somewhere to go back to. Everyone needs a home town. But where was I supposed to go? Throughout my life, I badly wanted to be from somewhere. Standing in the middle of Seoul, I knew that this was the city that had haunted my dreams as a child. The call to go back had always been there, but absence is not a static force in a person’s life. Absence exacts a toll. Not being in Korea for that many years had cost me any chance of ever being Korean again. And for what? There was never a time in all the years I lived in America that I was allowed to actually be American. My English was always second guessed. Not because I spoke poorly, but because no one could believe that a face like mine could ever be a native speaker. My soul always reeked of somewhere else. It didn’t matter what I said. No one believed me, because no one wanted to. I learned from them to not even believe myself.

Yet here I was in the old country, and I still could not lay my burden down. It turned out that being sent away meant being sent away. You weren’t supposed to go back. The door only swung one way, and to act in defiance of that came at the risk of pain. The act of return meant facing the long record of your trauma head on. Being born there meant nothing anymore. Not because I did not have the culture, though I didn’t. Not because I didn’t speak the language, though I couldn’t. Not because I was too American, because I wasn’t. I had travelled thousands of miles, across more oceans than the earth could hold, and the reason I could not be a part of this place was the exact same reason that I wanted it so obsessively. I was a victim of loss. A total, obliterating loss. And the wound of all those things that I did not have stood as a permanent ravine between me and any hope of belonging. Going back taught me that no matter what I did, I could never go home again. There was no home to go back to.

It was a short term eternity. And when I left, I was distraught. I knew that now I would be forced to wander an even deeper abyss. I had tasted enough of this place to plague me with homesickness for it once I left, and I learned enough about my relationship with it to know that I would always be distant to it. I became internally displaced, and my heart bent every part of my world towards this resurgent gravity. Silence and meaninglessness crept through the door, and my life became one long funeral march. I wanted to bury my pain, but no one would tell me in whose cemetery it belonged.

Still, long after I receded into the deepening dark, I would recall that first morning there. When the trains cross from the north side of the city to the south, they have to come above ground to go over the river. It had been overcast that morning when I left the hotel, but when the train burst out across the Han, the sun had found its way through the clouds and flooded in through the wide windows of the car. The light washed over me, and it felt as if this were the first time I had ever really seen the sun. Time and emotion broke across my body. The full realization of where I was swelled up inside of me. The frozen hell that had encrusted my life shattered. My chest heaved, and I threw my hands over my mouth to try to hold everything in. But it didn’t matter. My broken heart roared against the morning calm. And as I looked around at the faces of all these people that I spent a lifetime missing, I crumpled in my seat and cried.

I believed, truly believed, that it would bring an end to the ceaseless longing that had haunted my entire life. I thought that, for the first time, I would find a people among whom I would belong. I thought that I would find my family, and the litany of questions I had carried with me throughout the years since I was sent away would finally be answered. It was the last and, really, only great hope of my life. After all those years of manning the farthest outposts of alienation, I was going to return home. I hungered for a taste of what home was supposed to be. I wanted to savor the salt of Koreanness on my tongue. To roll those emotions around my mouth and feel the satisfaction of belonging drip down the walls of my heart. At that point, I had lived so many lives as so many different people, and I desired to be only myself. I would slip past the flaming sword into my own private Eden. I would eat the overripe fruit of my history, and be free of the lonely wilderness. Of course, dreams are a poor substitute for reality. And when I finally returned to Seoul after a lifetime away, I would discover just how foolish my dreams had been.

I was sent away on November 17, 1984. Adopted to America and erased from Korea.

When I arrived in the States, I was given a new name. An American name. A name that would not make anyone uncomfortable in the rural Louisiana backwater where I was taken. From then on, I would no longer be Kee Byung-keun. That identity would be put into hibernation for many years, and I would have to live as Clayton Glen Franks.

Of the constellation of scars on my soul, few have been as stubborn and painful as the name that was forced upon me. Said plainly, I hate it. Sanctified by legal bureaucracy and minutia, there is no easy way to rid myself of it. But oh, how I have dreamed of tearing this brand from my body, because ensconced in those lily white syllables is the spectre of the good American child I could never be. A son of the American South and not South Korea. A son for whom country roads would be a place of comfort and nostalgia, not anxiety and fear. I was given a white name to paint over what I was. But it never saved me from the unfortunate fate of being a minority in America, and within that alabaster cage, I burned.

For years, I was asked if that was my real name. They wouldn’t believe it, always assuming that there was something more. No one is comfortable with not knowing. Secrets make people uneasy. Like they are missing out on something important. Or worse, they worry the secret may be about them. And, of course, the suspicions are not unfounded. The name I used in America was always little more than make believe. I am not who I say I am. I never have been. But behind the constructs of this endless fiction are even deeper lies.

There is no one actually named Kee Byung-keun. It was merely another person’s projected idea about who I should be. A function of paperwork, not of heritage or love. There is no family that it is attached to. No long line from whose threads I have spent my life dangling. It is merely another symbol of my dispossession. Another reminder of all the things that were taken away.

I had spent every day of my life laying amid the bones of my story. What were talked about as hopes, were really fears. Not so much the fear that no one would ever call me home. But the fear that I was already there, and there would never be anyone else. That all my home would ever be was an empty house. Every day, I was filling my mouth with ashes, thinking that it would eventually turn into food. But when I could no longer stand the growl of my empty heart, I decided it was time to go back to Seoul to try and find something that would sustain me. If I was to survive, I had to leave.

It was still dark when I went to the airport. The rain was cold and the roads were empty. I did not look back as I disappeared into the terminal. What no one realized then was that this would be the last time they ever really saw me. Though my body would return soon enough, my spirit never crossed back over the Pacific again. It was the beginning of the end to my American life.

One of the few things that accompanied me from Korea as a baby was a small coin worth ten won. As I sat there that morning waiting to board my first connecting flight, I wished that I had it in my pocket to bring back with me. I would need something to pay the ferryman when it came time to cross the Styx. Instead, I would have to offer something else. Perhaps I could sign away my name or even my memories. There were so many things I wanted to be rid of then, and if giving up any of it would have brought me closer to home, I would have done it with glee. By the time I made it to the gate for the final leg of my journey, I was ready to leave everything behind.

It was November in Northeast Asia, the same month in which I’d been sent away, and when I stepped off the plane, it was cold. I can still remember the way the air bit into my skin. I can remember how the light rushed into my eyes like the water from a broken dam. I was home again. This was the country that birthed me, and every nerve ending in my body switched on to absorb it. Very little of those first moments has been lost in the intervening years. The anxiety, the anticipation; the frenzy of people outside of arrivals and the thickening guilt of not being able to speak to anyone in a language I should have known.

In my gut, I can still feel the heady mix of nausea and excitement as the bus left the airport for downtown. I can still see the flight attendant sitting a few rows in front of me. I can still feel the exhaustion in her bones and see the subtle slump of her shoulders, contrasted against her crisp celadon bow. I remember how full my eyes felt as we crossed the Han, and the city which was once and maybe still is supposed to my home bloomed in front of me. Every car swimming around us and every light flying above has been etched into the rigid bedrock of my mind. For the first time in my life, I was where I was. My footsteps were not echoing in some other city in some other country. I was there alone, and I had no idea what to do with a feeling like that.

Up to that point, I could count the Koreans I had known on one hand. Their presence amounting to little more than comets passing through the edges of my world. It bothered me deeply that I knew no one like me. It was as if every mirror I had ever stood in front of refused to reflect me. How can you know who you are if you cannot even see yourself? You live this life long enough, and you begin to ask whether or not you are even real. Am I a ghost? Am I an illusion? Among the many fictions that have burned across the surface of my life, is it possible that my own body is also an invented reality? You wonder and wonder and wonder, and then one day you look up and the mirror breaks.

I started walking. I had no idea where I was. I didn’t know what I was supposed to do, but I was looking. I couldn’t read anything. I couldn’t speak to anyone. I couldn’t do anything but propel myself forward, because everything behind me had begun to dissolve. There was no border to this image. No line that I would cross that would jar me awake. Along every possible axis, this place that I had dreamed of for so long sprawled out in front of me. And in every face, I could finally see my own. I was not a foreigner. I was from here.

The gravity of belonging pulled at every part of my body that first night. As a child, I was beat up for my eyes and my skin. I was dirty, ugly, and unwanted. I had been force fed a hatred for myself by a world that was willing to buy my body, but not respect it. I was ridiculed, slurred, mocked. I was derided as an interloper and a pretender. How dare I play at being American, because Americans do not look like I do. Every action of every day had become an act of defense. I felt endlessly besieged by a world that loathed me, and I could never be without my armor, because vulnerability was not something I could afford.

Even at home, among the people that raised me, I was alone. None of them knew what it was like to not be white. None of them knew what it was like to be constantly questioned as to why they were there and why they looked like they did. There was no refuge. There was no solace. No matter where I went or who I was with, no one understood the burden on my shoulders. No one could guide me through the storm of racism and prejudice that battered me everywhere I went. I was alone in my battle. I was alone in my pain.

So as I moved my body through the streets of Seoul, I felt something I had never experienced. Slowly and bit by bit, the armor that had accreted around me began to melt away. There had been no time in my life, no place I had been where everyone was Korean. Barely twenty-four hours before, I was still trapped in the cell of my American imprisonment, but here I was free. My race no longer mattered. It was not that I felt equal in the eyes of those around me. It was indifference. It didn’t matter to anyone that I was Korean, because they were all Korean too.

Every story has a beginning, and every story has an end. Before I became Clayton Glen Franks, I was Kee Byung-keun. Before I was Kee Byung-keun, I was someone whose name I do not know. I can only assume that someone, somewhere knows the name I was born with. But who they are and what they know are mysteries that will chase me to the grave.

On August 4, 1984, the continuity of my history was broken. The story as it was being told came undone, and a baby boy was abandoned in Yeongdeungpo Station on the south side of Seoul. There was no information. No note. No possessions. Only a yellow bag with a few diapers in it. Someone found the boy and took him in for the night. But the next day he was surrendered to the police and absorbed into the adoption system, in which he was processed and eventually sold to people in a country half a world away.

And so, I began where everything ended. On the morning of my first full day, I boarded the train and went back to Yeongdeungpo to see where it happened, to see where everything changed. I wanted to see if I could put myself back in the same physical place and perhaps remember something about that time. I wanted to remember something about the day when everything went wrong. Because while the narrative as it was recorded had no oxygen left in it, it was my body that had born witness to it. I had been in that place before. Someone had held me. Someone had found me. Someone had brought me in from somewhere and decided that this was the best possible place to leave a baby that was still too young to walk. It’s indulgent to think that this kind of memory is possible, because no one remembers that time in their life. But trauma does unusual things to the brain, and I really believed that being there would break the seal on the black box I was keeping these things in. I thought that I could defy the event horizon of my past and reach into the black hole with both hands to exhume the remnants of who I was before.

I walked every inch of every corridor I could find. I looked behind signs and into open lockers. I walked up and down the stairs and rode every escalator in and out of the station. I circled the building twice, and I wandered the neighborhood outside. I still think of a particular passage that was cordoned off. Its lights were dimmed until about halfway down where they came on again. I stood there for a long time thinking that this is either a metaphor or a warning, because down there where the lights came back on must be where my ghost was being kept.

In the end, I just sat in the waiting area for the express trains watching the passengers come and go. I thought that, if I waited long enough, I would see someone important. More than that, I wanted someone to see me. I wanted to be recognized by someone. I wanted someone to see my face and remember that day from twenty-six years before when they left me there with nothing. I was still in Yeongdeungpo; I still wanted to be found.

No one did. But from then on I developed the habit of looking at everyone on whatever train I would be on, wandering if this person sitting next to me might be the one that I had been searching for. Wandering if this person sitting next to me had also been searching for me.

There was a moment in my time there when I looked in the mirror of my hotel bathroom and I did not recognize the person I saw. Change normally takes time. Changing a habit or a lifestyle can take years, but sometimes change doesn’t take long at all. Before August 4, 1984, I had a history and an identity, but on August 5th, I had nothing. After all those years of thinking I would go home to Seoul and become who I was supposed to be, I found myself becoming someone else.

A new ache developed in my heart. In those long, lonely days when I couldn’t talk to anyone about anything, when I spent my mornings lost in the city and my afternoons languishing in my room, I felt the ache of almost. Here I was in the city of my birth, but because of the thick wall of the things I did not know, I was inhabiting it at a distance. I was almost there, but I didn’t know how to close the gap. I was almost Korean, but I didn’t know how to be one. I was almost home, but I didn’t know exactly where that was. I was finally somewhere that I should have belonged, but it was still just an almost. Something was still missing. I was not enough.

The initial relief of being among my people after so long away decayed into a nebulous disorientation. Everyone needs somewhere to go back to. Everyone needs a home town. But where was I supposed to go? Throughout my life, I badly wanted to be from somewhere. Standing in the middle of Seoul, I knew that this was the city that had haunted my dreams as a child. The call to go back had always been there, but absence is not a static force in a person’s life. Absence exacts a toll. Not being in Korea for that many years had cost me any chance of ever being Korean again. And for what? There was never a time in all the years I lived in America that I was allowed to actually be American. My English was always second guessed. Not because I spoke poorly, but because no one could believe that a face like mine could ever be a native speaker. My soul always reeked of somewhere else. It didn’t matter what I said. No one believed me, because no one wanted to. I learned from them to not even believe myself.

Yet here I was in the old country, and I still could not lay my burden down. It turned out that being sent away meant being sent away. You weren’t supposed to go back. The door only swung one way, and to act in defiance of that came at the risk of pain. The act of return meant facing the long record of your trauma head on. Being born there meant nothing anymore. Not because I did not have the culture, though I didn’t. Not because I didn’t speak the language, though I couldn’t. Not because I was too American, because I wasn’t. I had travelled thousands of miles, across more oceans than the earth could hold, and the reason I could not be a part of this place was the exact same reason that I wanted it so obsessively. I was a victim of loss. A total, obliterating loss. And the wound of all those things that I did not have stood as a permanent ravine between me and any hope of belonging. Going back taught me that no matter what I did, I could never go home again. There was no home to go back to.

It was a short term eternity. And when I left, I was distraught. I knew that now I would be forced to wander an even deeper abyss. I had tasted enough of this place to plague me with homesickness for it once I left, and I learned enough about my relationship with it to know that I would always be distant to it. I became internally displaced, and my heart bent every part of my world towards this resurgent gravity. Silence and meaninglessness crept through the door, and my life became one long funeral march. I wanted to bury my pain, but no one would tell me in whose cemetery it belonged.

Still, long after I receded into the deepening dark, I would recall that first morning there. When the trains cross from the north side of the city to the south, they have to come above ground to go over the river. It had been overcast that morning when I left the hotel, but when the train burst out across the Han, the sun had found its way through the clouds and flooded in through the wide windows of the car. The light washed over me, and it felt as if this were the first time I had ever really seen the sun. Time and emotion broke across my body. The full realization of where I was swelled up inside of me. The frozen hell that had encrusted my life shattered. My chest heaved, and I threw my hands over my mouth to try to hold everything in. But it didn’t matter. My broken heart roared against the morning calm. And as I looked around at the faces of all these people that I spent a lifetime missing, I crumpled in my seat and cried.